A big reason why this blog is called Adventures in 16 Colors stems from my fondness of (text) adventures on the C64. Price of Peril[sic] was the very first adventure game I ever played, and thus it's only fitting that it is also the first one featured on this blog.

Price of Peril is a German text/graphic adventure based on Robert Sheckley's science fiction short story The Prize of Peril. It was programmed in 1987/88 by Michael B. Schmidt who is better known as Smudo, one quarter of the German hip hop group Die Fantastischen Vier. That's a fine piece of trivia right there, something with which to dazzle and enlighten your friends.

The game made it onto the cover disk of INPUT 64's April issue of 1988.

INPUT 64 was a monthly German computer magazine for the C64 that came with a cassette tape or a floppy disk containing various programs. It ran from 1985 until 1988. While the focus was clearly on the provided software, most of the instruction manuals and other associated texts were printed on paper, thus I would not categorize INPUT 64 as a pure diskmag. INPUT 64 was a monthly German computer magazine for the C64 that came with a cassette tape or a floppy disk containing various programs. It ran from 1985 until 1988. While the focus was clearly on the provided software, most of the instruction manuals and other associated texts were printed on paper, thus I would not categorize INPUT 64 as a pure diskmag.Nevertheless, when it was introduced in 1985, INPUT 64 played a pioneering role in the evolution of the medium. At the time it was very common for German computer magazines to contain pages of program listings that readers had to manually type in. Michael Schmidt submitted Price of Peril as an entry for INPUT 64's adventure games competition which offered a reward of 3,000 DM for the winner. According to him, his game mainly won because it was the only submission that supported saving and loading the player's progress (source: Spieleveteranen Podcast #27). |

When starting the game for the first time you'll probably be very confused about what's going on, regardless if you can understand the German text or not. Price of Peril picks up right in the middle of the story without any explanation as to who you are or how you got here. Instead, the entire backstory has to be gleaned from the corresponding article in INPUT 64's paper magazine. One could say this was also a bit of a copy protection. Here's a brief summary:

We are in the distant future of 2013. Six years ago, the Voluntary Suicide Act was passed. This amendment gave birth to a flurry of high-stakes TV game shows that saw their candidates risk their lives. The Prize of Peril is one of the most successful of these modern gladiator shows. It features a candidate who is pursued by a ruthless criminal gang through the streets of New York City for exactly one week. If the hunted manages to survive for this long, he or she wins seven million US dollars. If the gang can kill the candidate before the time is up, they get pardoned. The chase is shown live on TV with cameras everywhere. Viewers can call the station and act as Good Samaritans by assisting the hunted candidate, or they can provide the hunters with information instead, if they feel so inclined.

Jim Raeder is The Prize of Peril's current candidate, and he has been the hunted for almost a week now. His adversaries are members of the Thompson gang, a vicious band of warped murderers who have been close on his heels for almost the entire time.

It is the morning of the final day. Jim found some respite in an abandoned apartment. He managed to sleep for a few hours, but he is at the end of his physical and mental strength. All that is left for him to do is to survive until 5 pm, but he knows that the Thompsons won't give up so easily.

And that's where the game starts. This is very similar to Robert Sheckley's original story which also begins in medias res.

What follows is a recap of how I played (and struggled) through the game almost thirty years ago. Since there is no English translation, I'll explain what's being said on the screen.

The game opens with a description of the aforementioned abandoned apartment. As is common in adventure games, the text is written in the second-person point of view, as if the program were addressing the player directly. Price of Peril also provides a picture of each location. One of the first things I had to learn about adventure games was that the picture didn't necessarily match with what was said in the text. Even if I saw a desk lamp, if it wasn't mentioned in the text, it simply didn't exist.

As I mentioned before, Price of Peril was the first adventure game I came across, and I was lucky that the article in INPUT 64 also contained a manual which explained in detail how to communicate with the program. Without those written instructions, I would've been at a loss right from the start and probably would've given up pretty soon.

Back to the game: The only objects explicitly described in the starting room are a portable transistor TV and a locked door. Since I don't have a key, and the game doesn't understand UNLOCK anyway, I can't do anything with the door. I can pick up the TV, however.

As soon as I make the first move, the game tells me that I can hear footsteps at the door. Price of Peril runs on a turn-based timer. Each command I type takes time which allows my adversaries to get one step closer to me. This is a cool way to make the game feel tense, but it can also be annoying if the parser misunderstands a sentence and causes me to waste a turn as a result.

I switch on the TV and, even though the image is distorted, I can hear the voice of Mike Terry, the host of The Prize of Peril, telling the audience that a helicopter outside is filming me right now. At the same time, somebody knocks at the door.

When I first played this at the age of 11, it took me an embarrassingly long time to understand that the game consisted of more than just one room. Even my parents tried to suggest commands, but this was their first text adventure as well and we didn't get anywhere. Only the next morning did I realize that I could type N or S to go into different rooms. I immediately went to my mother to share this amazing discovery, but having just woken up minutes ago, she was probably very confused about what I was talking about.

The text suggests that there are exits to the north and south. If I try any other direction, I get punished with a wasted turn. Since I've played this before, I know that I should go to the south first.

This is a small storeroom with a lot of junk in it. Unfortunately, there are no windows or any other means of escape from here. Among the rubble, the game points out several items: a baseball bat, a couple of empty bottles, some old newspapers, an envelope with a stamp on it, and several cardboard boxes.

Meanwhile, Mike Terry's voice from the TV announces that a Good Samaritan just called in with some helpful information for me. At the same time, the people outside the apartment are trying to break open the door. I guess they're not Jehovah's Witnesses, unless their evangelist methods have become unusually aggressive in 2013.

There isn't enough time for me to pick up everything in this room. I can take exactly two objects with me, but there is no way for me to know in advance which ones are going to be needed later on. I won't be able to come back here if I get the wrong items now. I'll grab that baseball bat, so I have at least something to defend myself.

The Good Samaritan gets on the air and explains that he used to live in the apartment I'm currently in. The game also tells me to hurry up, as the door in the other room starts splintering.

The second item I'm picking up is the envelope. Trust me, all will become clear later on.

The voice from the TV tells me that there used to be a window in the bathroom. I can also hear angry shouts coming from the other side of the increasingly damaged door, but the game doesn't want to reproduce the explicit language being used. If it had, INPUT 64 probably would've asked the author to take the offending words out.

It'll take me two turns to get to the bathroom. One step to the north brings me back to the starting room. The Good Samaritan adds that I can't see the window in the bathroom because it's been painted over. The door is about to break down, and the game gets snarky at me, telling me it's too bad I don't have anything to write my testament. At least I have a stamped envelope to mail it.

The bathroom is a mess of garbage and dust. I don't have any time to appreciate the filthy scenery because behind me the Thompson gang just broke into the apartment and they're about to fire their weapons in my general direction. At that moment, the guy on the TV provides me with the final clue: To escape, I just have to jump against the wall.

The game is very peculiar about this piece of information. If I immediately go into the bathroom and try to jump against the wall, the parser pretends not to know what I'm talking about and reacts with a bewildered "Wie bitte?" ("Pardon?"). The command only works when the TV is turned on and the Good Samaritan tells me what I need to do.

My death-defying leap through the painted-over window leads me into a small courtyard. The rough landing on hard concrete leaves me stunned for a moment, giving the gangsters enough time to get to the broken bathroom window and take aim. Before the Thompsons can open fire, several smoke bombs go off around me and instantly plunge me into a dense cloud of white. The TV exclaims that these bombs were donated by another Good Samaritan who is now being asked how she feels about just having saved someone's life.

I'm left with exactly one turn to escape from the courtyard, but the room description conveniently forgets to tell me in which direction the exit is. The picture isn't of any help either. On the contrary, I find the excessive placement of windows rather unsettling the longer I look at it.

Something I should probably clarify is that in text adventure games the term "room" is used for any location, regardless if it is an actual room inside a house or an outdoor area, like a forest or a city street.

Anyway, the only direction that doesn't lead to early death is to the west.

I leave the courtyard behind and enter Manhattan's 63rd Street which, according to the text description, leads north and south. I think the avenues are supposed to run north to south, but whatever, this isn't a tourist guide. Also, I'm told that I feel hungry and tired which probably doesn't help my sense of direction.

Case in point, if I go south from here, I somehow manage to walk straight into a dead end. Even the text description is taken aback and literally goes "OMG! A dead end...".

There's a helpful DEAD END sign to let me know that this alley indeed culminates in a massive brick wall. I can't shake the impression that the game just wants me to believe there is no other way out of here, so I try once again to jump against the wall. This time, all I get is a "Wie bitte?", though.

All right, let me go back to the street.

Oh. I walked right into the Thompson gang and got deadened. The game shows its snarky side again and comments how my death is a suboptimal solution to end the hunt.

Price of Peril is very linear to the point where any kind of backtracking results in instant death. This is justified by the narrative, as the gangsters are always just one or two steps behind the player. The constant danger certainly adds some welcome tension to the gameplay experience, but anyone trying to solve the game without a walkthrough will see this gravestone a lot.

Let's see what happens if I follow 63rd Street north instead.

Visually, the street hasn't changed at all, but the description mentions a man who is window shopping here. If I talk to him, he directly tells me that he is a stamp collector. Consequently, I take out my baseball bat and hit him over the head. I mean, I offer him my envelope and get some money in return.

| Here's an interesting anecdote Michael Schmidt revealed in the podcast I linked to earlier: Initially, the money puzzle worked differently. Instead of taking the envelope from the storeroom and giving it to the stamp collector, the player had to pick up the baseball bat and clobber the poor pedestrian unconscious in order to steal his wallet. Heise Verlag, INPUT 64's publisher, was not particularly happy with this solution and asked the author to replace it with a less violent puzzle. |

Further north, I come across a taxi stand with several cabs vying for my attention. The taxi in the picture is a sprite, by the way.

After entering one of the cars, I get immediately asked by the driver to hand over some money. I don't think that's how taxi fares work, not even in 2013, but it is possible that the driver recognized my face and wants cash in advance for driving a hunted man around. If I don't present any money, I get kicked out of the taxi and stumble right into the Thompson gang who doesn't hesitate to kill me.

Since I'd like to survive a bit longer, I pay the fare in advance. The driver asks if New Salem is an agreeable destination to which I say yes. Anything else just leads to another death.

The ride has barely begun when a car approaches the taxi from behind and tries to overtake it. Unsurprisingly, the vehicle is filled with members of the Thompson gang, and they'd like to get a good look at this cab's occupant.

I open the taxi's passenger door which nets me an angry comment from the cabbie, and I throw myself out of the driving car.

The violent impact on the pavement leaves me breathless for a minute, but the gangsters apparently haven't noticed my stunt, as they continue following the taxi. I get up and assess my situation: To the west is a forest which might be part of Central Park and to the east is a house from which I can hear Mike Terry's voice.

I approach the house and get invited inside by a friendly lady who recognizes me from watching The Prize of Peril. She offers me some food which I thankfully accept. I always thought this detour was necessary so I wouldn't collapse from hunger later on, but upon replaying the game I've come to realize that I can skip this part without any repercussions.

There is nothing else I can do in the house, so I leave and go west into the forest.

One might think that this area would be the perfect hiding place from a bunch of city thugs. Unfortunately, the Thompsons came back just in time to see me disappear into the trees. Bullets fly past my head and bury themselves into the nearby trunks. The only direction that doesn't lead to more trees (and immediate death) is to the south. The parser becomes weirdly picky at this spot, or at least even pickier than usual: If I type in anything else than "S", even if it's just random letters, I die. Until now, if the parser didn't understand what I was saying, it went "Wie bitte?" and didn't count my command as a valid turn.

Looks like I've come across a church, of all things. Are there churches in Central Park? Maybe there are in the distant space year of 2013. Okay, I'll stop with that joke now. In any case, this building is my best bet to escape the hail of bullets being fired at me, at least for a while. However, if I run south toward the building, I get shot in the legs and die. How can I prevent this from happening? Do I whip out my baseball bat and try to deflect the shots like a Primitive Technology Jedi? No, I have to duck, even though the game just told me the gangsters were shooting at my legs.

I run inside and make my way down the nave toward the exit to the graveyard. Do the Thompsons respect the sanctity of a church? They just opened the entrance door and started firing at me, so I take this as a no. If I continue to run, I get hit. Once again, I have to duck first to evade some unhealthy doses of lead and then make a dash for the southern exit.

I enter a badly maintained graveyard whose flimsy-looking and lopsided tombstones remind me of the cemetery set from Plan 9 from Outer Space. There's no time for an unconvincing double of Bela Lugosi to enter the scene, though, as the gangsters are right behind me. The first thing I need to do is, you guessed it, duck. However, if I now try to go south again, the game tells me that I ran right into my pursuers. I think this room got its cardinal directions confused. This bug is of no consequence, though, as no matter in which direction I take off, the gangsters shoot me down. The only way to escape their bullets is to dive into the open grave.

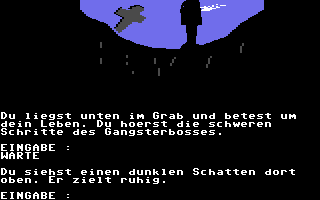

This looks much larger from the inside. The grave is deep enough that I'm completely out of my pursuers' sight. Unfortunately, there is no hidden exit down here. All I can do is listen to the heavy footsteps of the Thompsons' leader who is slowly approaching what might very well be my final resting place.

A black silhouette appears at the grave's brink and I can make out a steady hand that points a gun right at my head.

Apparently, if I don't move any muscle, the gangster takes longer to aim, and that's just enough time for the clock to reach 5 pm. Mike Terry's voice booms out from above, magically amplified by concealed speakers. He orders the Thompson gang to cease fire immediately, as I've just survived for long enough to win The Prize of Peril. The game ends with a cute animation that shows me climbing out of the grave and doing a little victory dance while a studio helicopter flies past in the background. I am wearing what looks like an orange jumpsuit. No wonder the gangsters kept on spotting me with a garish outfit like that.

And that's Price of Peril. As adventure games go, this is quite a short experience. I tried a speedrun earlier, as ridiculous as that may sound, and finished the game in 1 minute and 52 seconds. This stands in stark contrast to how long it took me to finish the game for the first time, without looking at a walkthrough. That's old-school adventure games for you.

Naturally, almost no text adventure games came with a map of all the rooms, as that would've spoiled the experience. The player was expected to sketch out a map of their own, armed with pencil and graph paper. I don't think I ever drew a map for Price of Peril. The small number of rooms was easy enough to memorize. Regardless, I've now made a map in digital form, just because I think it's interesting to see a complete overview of a game that only ever shows one scene at a time:

| THE PRIZE OF PERIL How close does the game adhere to the original short story by Robert Sheckley? I got to read it only recently and realized that many of the game's scenes were adopted almost verbatim, like the escape from the apartment or the finale in the graveyard. The frantic pace of The Prize of Peril lends itself very well to a linear, mainly event-based adventure game. Aside from the backstory printed in the INPUT 64 magazine and a few sarcastic comments in various Game Over screens, the game largely drops the satirical aspects of the original story. For example, there's a scene in The Prize of Peril where Jim Raeder, the hunted candidate, is temporarily rescued by a Good Samaritan in a car. It turns out the selfless helper is working for the TV network, and she reveals to Jim that the studio is manipulating the events as best as it can. They want to keep him alive and thus maintain the show's high rating. They want him to win without making their meddling too obvious. The Thompsons were told to go easy on him, but if he doesn't put in a better performance, they'll have to kill him sooner rather than later. She sums it up with "If you can't live well, at least try to die well." The Prize of Peril was first published in 1958, predating survival shows and reality TV by decades. |

CONCLUSION

This is a tough game for me to judge. It's a good thing that I'm not writing "objective" reviews here, thus I can let nostalgia slobber its deceptive juices all over my opinion.

Price of Peril was the first text adventure game I ever played. As flawed as it is, I still think I was lucky that this game, in particular, introduced me to the genre. Before it, I hadn't been aware that games could tell stories that went beyond your usual save-the-princess fare and depict worlds that consisted of more than a couple of platforms with enemies on them.

I still remember the reactions I had to certain events in the game. For example, when I successfully escaped from the apartment and saw the streets of Manhattan for the first time, I was in awe. This game had suddenly become much bigger than I had anticipated. Of course, I soon realized that I could only walk down this one street, but I still felt that the game's scope had expanded significantly.

Being mainly a text-based game, Price of Peril isn't going to win any prizes in the graphics department. The pictures consist of basic shapes and lines, but they don't look awful. The author shows some grasp of basic perspective, which is already more than I can say for many contemporary titles. Michael Schmidt had to make his own drawing tool to create the game's pictures, and in their compressed state they all fit into the C64's memory. That means they don't have to be loaded from disk each time the location changes which improves the game's flow considerably.

There is no background music, nor are there any sound effects. That's completely fine by me, I don't expect an orchestral soundtrack in a text adventure anyway.

When it comes to gameplay, there is quite a bit to criticize: The parser is rather basic, and the game relies a lot on instant death traps that can only be avoided with luck or player clairvoyance (i.e. repeated attempts). However, these flaws probably sound more severe than they actually are. The game is so short that, even if you don't use the save/load feature, it takes no time to get back to the spot where you previously died.

Unbeknownst to me, this short and very linear piece of interactive fiction managed to put me through the complete spectrum of emotions that an old-school adventure game can evoke. I felt frustrated when I got stuck and died over and over. I was ecstatic every time I managed to get past a puzzle, and every new room picture felt like a reward in itself. I mulled over possible puzzle solutions even when I wasn't playing the game.

Adventure games are generally known for being a slower-paced genre. In that regard, Price of Peril is an unusually eventful game where one action scene follows another, and the player can die in just about any situation. Unfortunately, it doesn't translate well to a fair gaming experience, especially because the parser doesn't understand a lot of commands. That didn't stop me from enjoying the game, though. In fact, I liked it enough that the whole genre would soon become one of my favorites on the C64.

No comments:

Post a Comment